AS

I WALKED OUT

ONE MIDSUMMER MORNING -

LAURIE LEE

You can tell a book is going to be good when it immediately evokes

memories, thoughts and feelings from the well of your being, and As

I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee is one such

book.

Just a few pages in and I'm reminded of setting off for the

Stonehenge Free Festival one sunny morning and at the bottom of my

street bumping into a school friend who was on his way to his

apprenticeship at the local factory. "Where are you going?"

he asked me as he eyed-up my rucksack and sleeping bag. "I'm

going to the Stonehenge festival," I told him. And the look he

gave me was one of incredulity and envy, as if to ask 'How is such a

thing possible?'

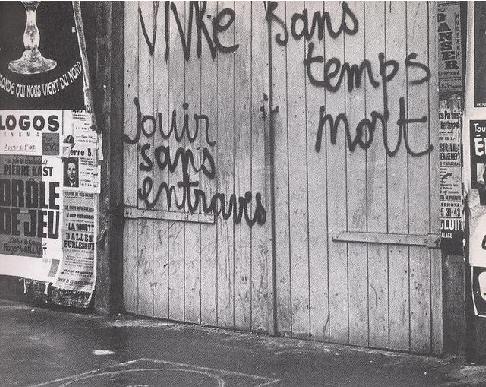

I'm reminded of when I was but a boy at school and my first

experience of a riot. The police had for some reason invaded the

council estate where I lived and were having bricks thrown at them by

local youth. I was in amongst the crowds watching the goings-on when

a large brick arced through the air and landed full-square onto the

windscreen of a police riot van, causing it to cave-in with an

almighty bang and smash into a thousand cubes of glass. The crowds

roared their approval and I suddenly thought - my god, this isn't

vandalism, or a criminal act, or anything bad in the slightest, my

god - this is an act of freedom.

I'm reminded of J18 in the City of London years later - pre-Seattle -

and devastating the Square Mile, smashing the banks around the Stock

Exchange and raining bottles and bricks down upon the police. Knowing

that day we were finally free of trying to win arguments or of

spreading any message and even of the whole idea of 'protest'. This

time round we were simply on the attack and destroying what we hated.

We were on a whole new road... to freedom.

I'm reminded of when as a teenager and living as a traveller on

Crete, sleeping on beaches and on mountains, and one day talking to a

Greek boy who said "I want to be like you, Johnny. I want to be

free."

From his village in the Cotswolds via Southampton, Laurie Lee walks

to London where he acquires a job on a building site. This, for a boy

with limited experience of life beyond the confines of family and

village is an adventure in itself but he doesn't stop there. When the

job comes to an end he decides on a whim to hot-foot it over to

Spain, choosing to go there of all places in the world because he

knows the Spanish phrase for 'Will you please give me a glass of

water'.

All very well, you might think but what's so interesting about a

story like this? Well, it's the fact that it's based on his own life,

the fact that it's beautifully written but above all, it's the fact

that it all takes place in the Spain of 1935, one year before the

outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

There's a hint of what's to come when Lee first arrives in London and

the only address he knows is that of an old girlfriend from his

village whose father lectures him on the theory of anarchy and the

necessity for political and personal freedom. Apparently, the father

is a Left-wing agitator who'd recently fled from America having been

involved in 'some political trouble'. Unfortunately it's not

made clear who this might have been in real life.

On arriving in Spain, Lee spends a year traversing the country on

foot, encountering Spanish peasantry, fellow foreign travellers,

ex-pats, vagabonds, madmen, angels, beggars and idiot savants, as

well as witnessing stunning beauty and horrific poverty. It's the

poverty and inequality, however, that in the scheme of things turns

out to be the most important, as Lee explains:

'Until now, I'd accepted this country without question, as though

visiting a half-crazed family. I'd seen the fat bug-eyed rich gazing

glassily from their clubs, men scrabbling for scraps in the market,

dainty upper-class virgins riding to church in carriages,

beggar-women giving birth in doorways. Naive and uncritical, I'd

thought it part of the scene, not asking whether it was right or

wrong. But it was in Seville, on the bridge, watching the river at

midnight, that I got the first hint of coming trouble. A young sailor

approached me with a 'Hallo, Johnny', and asked for a cigarette. He

spoke the kind of English he'd learnt on a Cardiff coal boat,

spitting it out as though it hurt his tongue. 'I don't know who you

are,' he said 'But if you want to see blood, stick around - you're

going to see plenty'.

It's not clear whose blood the sailor is referring to and it's only

later on in the book that the subject is returned to when Lee is

working at a hotel and he gets to talking to his Spanish waiter

friend:

'He talked about the world to come - a world without church or

government or army, where each man alone would be his private

government. It was a simple, one-syllable view of life, as black and

white as childhood, and as Manola talked, the fishermen listened,

bobbing their heads up and down like corks. Their fathers had never

heard or known such promises. Centuries of darkness stood behind

them. Now it was January 1936, and these things were suddenly

thinkable, possible, even within their reach.

But first, said Manola, there must be death and dissolution; much

had to be destroyed and cleared away. Felipe, the chef, who liked

food and girls, was the pacifier, preaching love and reason. No guns,

he said; they dishonoured the flesh; and no destruction, which

dishonoured the mind. Everyone knew, all the same, that there were

now guns in the village which hadn't been there before.'

As the book ends, the Civil War begins in earnest only for Lee to be

whisked back to England by a Royal Navy destroyer sent out from

Gibraltar to pick up any British subjects who might be marooned on

the coast. The Spanish villagers whom Lee has been living with all

urge him to go with the ship, viewing it as the King of England

himself sending for Lee and that he was the most fortunate of men for

this.

On board the ship, Lee sees a German airship passing over in the sky

above, a swastika black on its gleaming hull. Back in England,

looking at the Civil War from the outside in he begins to understand

the scale and the implications of the war, with Germany and Italy

lining up to militarily support Franco and the Spanish Fascists

whilst England and France busied themselves by advocating appeasement

and non-intervention. The Spanish anarchists and their fellow

citizens that Lee had come to know so well during his travels were

being hung out to dry by the democratic powers and left at the mercy

of the Fascist powers.

For Lee there is only one thing to do, and that is to return to Spain

to join the International Brigades. And there the book ends with Lee

crossing the Pyrenees and re-entering Spain - with a winter of war

before him.

The Spanish Civil War has been called "the first battlefield"

and can now be seen as a rehearsal for the Second World War where the

triumph or defeat of conflicting ideologies was at stake. It was one

of the few times in history that Anarchism and a genuine will to

freedom lived and flourished only for it to be crushed by the

superior fire-power of the supporters of Fascism.

If only that freedom had been supported and defended by Britain and

France in the same way that the Fascists were supported and defended

by Germany and Italy then the course of the world could have been

altered and the blood bath of World War Two perhaps averted.

Ultimately, the lessons of the Spanish Civil War are glaring and

relevant even to this day and age. Particularly, even, to this day

and age.

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning is about freedom; the dream of

it, the sense of it, the quest for it, the grasping of it, the

fighting for it, and the defending of it. It's about the idea of how

life could and should always be. It's about other worlds that are not

only out there already but other worlds that are not out there but

are possible.

Laurie Lee had no other choice but to return to Spain because within

him already was a flickering spark of freedom that he fanned by him

upping sticks and walking to London but which then burst into fire by

his travels through Spain. And once that flame was lit there was no

extinguishing it.

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning is a very beautiful and very

special book indeed.

John Serpico